In the fall of 1995, I was about to turn nine years old and was in the third grade. That was the year I was placed into what we called PELICAN—Pursuing Excellence through Learning Innovation, Cognitive and Affectionate Nurturing. It was a program for the “smart” kids who tested well, designed to challenge us and help us develop beyond the standard curriculum. Being part of this select group meant access to the (new at the time) computer lab at our elementary school, mostly for math and word games.

One day, however, our teacher had a special treat: she was going to teach us how to use the Internet.

As she guided us through Netscape Navigator and explained the power of information suddenly at our fingertips, the possibilities were already forming in my little mind. The idea that anything I was curious about might already exist somewhere out there, just waiting for me to discover felt equal parts overwhelming and magical. Near the end of class, she had each of us come up to her computer individually and choose something we were interested in. She would search for it and show us how to find information online, like a librarian unlocking a secret room.

While TLC, Alan Jackson, and the Carolina Panthers (in their inaugural season) were popular choices among the third graders of Homewood Elementary, I knew exactly who I needed to know more about. I had only seen him wrestle once or twice, but every time his image appeared in Pro Wrestling Illustrated or Inside Wrestling, I felt a strange mix of intrigue and unease. He didn’t look like the other wrestlers I knew. He didn’t smile. He didn’t pose. He was covered in scars and strapped to a gurney before matches, seemingly as much for the safety of the audience as for that of his opponent. He looked dangerous in a way I didn’t yet have language for.

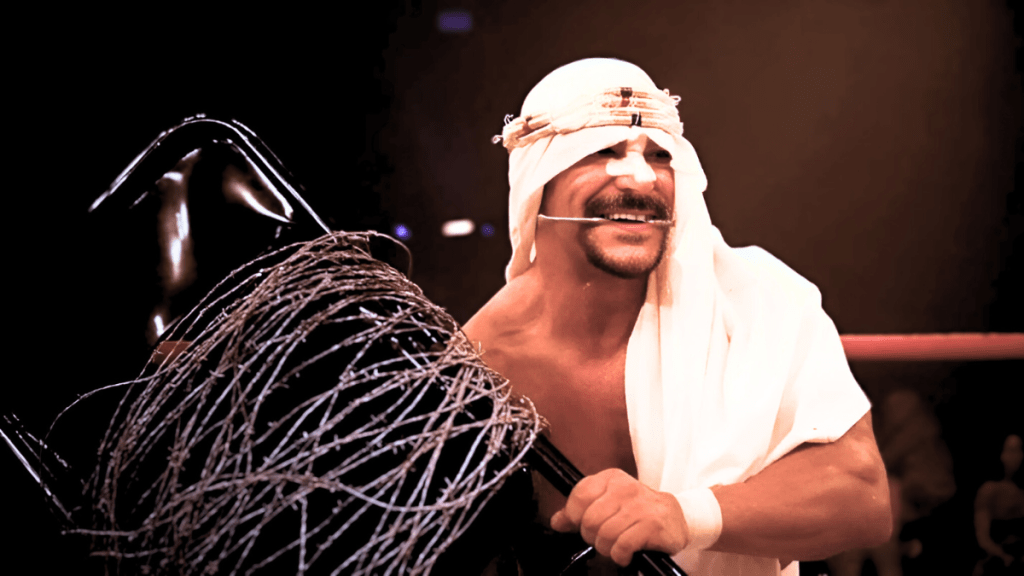

I needed to know more about the homicidal, suicidal, genocidal, death-defying Maniac: Sabu.

Sabu was unlike anything that had come before him. He wrestled with an incredibly reckless, violent style that often seemed—even within kayfabe—like he was doing more damage to himself than his opponent. He dashed around the ring and launched himself off ropes, chairs, guardrails, and anything else he could get halfway footing on (and often things he couldn’t). Watching him felt less like watching a match and more like witnessing a car crash unfold in slow motion. He moved like a junior heavyweight but carried himself like a force of nature.

At first, I could only follow his exploits through magazines and his brief, underwhelming WCW run, where he was never given the opportunity to show what he was capable of, thanks to the politics of wrestling and WCW’s desire at the time to only appease its top stars. However, the photos and articles I was able to see in Pro Wrestling Illustrated, and other publications painted the picture of someone truly unhinged. This wasn’t a wrestler, it was a weapon in human form, and I was immediately drawn to him.

By early 1996, our cable company carried a sports station out of Atlanta that aired ECW late Friday or early Saturday at 2 a.m. I watched as often as I could, depending on whether I managed to stay awake. (Cut me some slack, I was nine.) It was only available at my mom’s house, so on those weekends I did whatever I could to stay up late and sneak out to the living room. Stealing sodas from the fridge, trying coffee for the first time, a nap immediately after school on Friday, I tried it all to make sure I could be awake to see it. If I had known what cocaine was back then, I probably would have considered it just to get my hour of Extreme. There was always the low-grade anxiety of being caught, which only heightened the experience. Sabu didn’t feel like something meant for kids, which of course made him feel even more important. This wasn’t Sting on a Saturday evening, it was a secret, and it felt like it belonged to me. My mom never explicitly forbade me from being up late like that, or watching anything on TV, but I was a smart enough nine year old to know this was NOT appropriate viewing for a child my age.

Once I could see him in action, especially in ECW where he was presented with an aura that made him feel like an unstoppable star, my fearful intrigue gave way to amazement. Paul Heyman (the creative force behind ECW) presented him like a truly dangerous madman. He never spoke and any time he appeared on screen, he was talked about as if he could do something both fantastic and violent at a moment’s notice. He wasn’t just surviving the chaos, he was creating it, shaping it, daring the audience to look away. In 2026, it’s no longer out of place to see tables used for big spots, springboard offense, moonsaults, or even barbed wire. While Sabu did not invent these elements, he was their codifier.

His use of tables is the most obvious antecedent to modern wrestling, where many shows can’t go on without at least one or two being broken, often accompanied by Pavlovian “We Want Tables” chants echoing through the arena. (Another ECW influence, I didn’t say they were all positive.) While territories like Memphis and Southwest utilized them occasionally, as did Randy Savage and Terry Funk in the 80’s. What Sabu did with tables was akin to what bands like Nirvana, and Pearl Jam had done with the Poisons and Ratts that ruled the music world in the 80’s. Those table spots in the ’90s paved the way for TLC matches in the Attitude Era, the formalization of “Tables” matches, and all those times Christian and Randy Orton just couldn’t break one. If we keep this analogy going, that makes Randy Orton akin to Nickelback which seems appropriate.

Barbed wire in wrestling certainly wasn’t his invention, but it was his domain. What had once been a southern territory staple became an art form in his hands. The infamous 1997 Terry Funk match at Born to Be Wired was so gruesome that they famously never ran another, yet the tape sold like gangbusters. Watching it felt transgressive, like seeing something you weren’t quite supposed to see. Sabu tore his bicep early in the match on the barbed wire and used surgical tape at ringside to tape the injury and finish the match. I was horrified and couldn’t look away; it was a shining example of doing whatever it took to get something done, even if it kills you. Even at that age, I could tell this wasn’t about winning. It was about endurance, about what someone was willing to give up in front of an audience. Sabu worked in tables and barbed wire the way other artists work in oils or watercolors—each scar was part of the canvas.

Sabu was too dangerous a performer and too independent to ever have a sustained run outside of ECW, but that was never the point. While he held championships, the real draw was always the act. He knew exactly what got his character over and spent years afterward earning paydays by “playing the hits,” his reputation doing as much work as his body still could. That all seemed to culminate in the 2006 ECW revival.

By then, in the eleven years since learning how to use the internet, I had become pretty adept and was devouring every rumor I could find. Heyman was booking with real money. We had RVD, Kurt Angle, a young indy hotshot named CM Punk, and we had Sabu. For a moment, it felt like the past and present were colliding in the best possible way.

The bloom came off the rose quickly. After the arrests of Sabu and RVD, the end was already in sight. Just weeks after the launch of the brand, RVD and Sabu were traveling together and were arrested for possession of a controlled substance and drug paraphernalia. It may be shocking to find out that a guy who referred to himself as “Mr. 420” (RVD) would enjoy Marijuana. Unfortunately due to WWE (and the United States in 2006) archaic policy, they would be suspended. While RVD was a big enough star to stick around near the upper midcard, Sabu would quickly find himself out of management’s favor, and his career trajectory would quickly roll downhill. I was even in attendance at the notorious December to Dismember pay-per-view, where Sabu was pulled from the Elimination Chamber match in favor of Hardcore Holly. It felt deflating in a way that was hard to articulate at the time—another reminder that the version of wrestling I loved was always slightly out of step with the one that existed. I’m always going to want more Sabu and less Bob Holly, and I’m always going to like the look of wrestling in front of 1000 rabid people above 5 or 10,000 bored people who just want to sing along to entrance music. It’s the curse of coolness that plagues anyone drawn to things labeled “alternative.”

In wrestling, just as in music, film, fashion, or any other art form, the story is as old as time. Someone does something radically different, and it ignites passion in those who see the medium being pushed somewhere new, while provoking backlash from those who feel the break with tradition is so severe it should be considered something else entirely. Eventually, that exciting new thing is defanged until it’s fit for consumption.

Mapplethorpe becomes Banksy.

GG Allin becomes Green Day.

And Sabu becomes any number of faceless guys flipping through tables.

Liking Sabu trained me early to accept that the things I loved most would never quite belong to me forever. That eventually, they’d be diluted, misunderstood, or flattened into something easier to sell. But it also taught me that seeing something before it was safe was a kind of privilege.

Eventually, Sabu returned to the independent circuit, working anywhere that would meet his fee. He died on May 11, 2025, and it hit me harder than I expected.

Being a fan of this thing means getting used to death. Thankfully, those losses seem less frequent now than in the ’90s and early 2000s, when it felt like every few weeks another childhood hero’s enlarged heart finally gave out. As they’ve become rarer, and as I’ve gotten older, they’ve begun to cut deeper.

An integral part of my childhood was gone.

What surprised me most, though, was the outpouring of work dedicated to his legacy. Fans shared art, old music videos cut to his highlights, long-form essays about his impact, and hours of podcasts devoted to this man who had captivated me decades earlier. It felt like watching people grieve in the only way wrestling fans really know how—by remembering everything.

Sometimes it feels like our experiences are wholly unique. What I love about professional wrestling is how it dispels that illusion, offering the realization that countless others were moved by the same beauty and violence that compelled me all those years ago. That something so chaotic could also be communal still feels miraculous. Wrestling will keep moving forward, finding new ways to shock and reinvent itself. New fans will fall in love with new crazy highspots, new jacked bodies, new ideas of what’s possible. Some of them will probably never know Sabu’s name, even as they cheer for the echoes of his work. That’s the strange bargain of influence: you disappear so the thing you created can live on.

Sabu was revolutionary. His influence spread so far and wide that his DNA is embedded throughout modern wrestling, to the point where many newer fans don’t even realize what they’re watching was pioneered by this man. His work has been sanded down, made safer, packaged for mass consumption, yet that blueprint remains.

The Genghis Khan of professional wrestling.

The first thing I ever looked up on the internet was Sabu.

The second thing I ever looked up was “Sabu wrestler,” after my initial search returned only results about the actor.